Kumano Oji Shrines

What is an Oji?

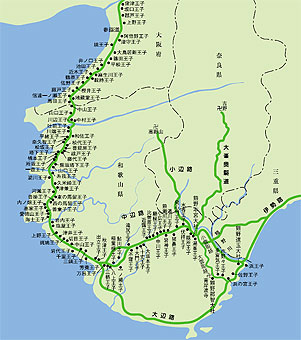

Oji are subsidiary shrines of the Kumano Grand Shrines that line the Kumano Kodo to protect and guide pilgrims. These shrines house the “child deities” of Kumano and serve as places of both worship and rest. The formation of these shrines has been attributed to the Yamabushi mountain ascetics, who historically served as pilgrimage guides.

Oji Classification

As a set, they are referred to as the “Kyujukyu Oji”, or “Ninety-nine Oji”. This figure is an expression alluding to the large amount of shrines and is not an exact number.

Of the numerous Oji shrines, five are considered to be the most prestigious and are called the Gotai Oji:Fujishiro-oji, Kirime-oji, Inabane-oji, Takijiri-oji, and Hosshinmon-oji.

List of Selected Oji Shrines

Takijiri-oji

Takijiri-oji is a very important spot on the Kumano Kodo Pilgrimage route and one of the five major Oji shrines. It is here that the passage into the sacred mountains begins—the entrance to the abode of the gods and Buddhist paradises of rebirth. There were once extensive halls, a bath house, lodgings for pilgrims, and residences for priests, priestesses and monks located here.

It was here during the golden age of the imperial pilgrimages to Kumano (12th & 13th centuries) that severe cold-water ablution rites were practiced repeatedly to purify body and spirit before worshipping. During the elaborate ceremonies that followed, sutras, prayers, dancing, sumo and poetry were offered to a mixture of local and Buddhist deities.

The two rivers that converge at Takijiri-oji play an important role in the historical and spiritual aspects of the shrine. “Takijiri” means “base of the waterfall,” a reference to the nearby confluence of the Tonda (Iwata) and Ishiburi Rivers.

According to some traditions, one was associated with Sanzu-no-Kawa, the mythical river that separates the land of the living from the land of the dead.

In a document from the early Kamakura era (1185-1333), the river to the right of the Oji was the realm of the silent prayers of Kannon, the Bodhisattva of Mercy, and in the river on the left flowed divine waters that could cure all ills.

Chikatsuyu-oji

Chikatsuyu-oji is located in a large intermountain basin (elevation: 300m) bisected from North to South by the Hiki-gawa River, approximately halfway between Takijiri-oji and Hongu. It is one of the oldest Oji shrines and a major site along the Kumano Kodo.

Over 900 years ago, during the peak of the imperial pilgrimages to Kumano, parties of up to 300 people would be accommodated in the area. They performed cold-water purification rites in the river before worshipping. The buried remains of 13th-century religious artifacts were discovered close by, and until 1906 a large pavilion was located at this site. It was dismantled because of an imperial edict to merge shrines.

Tsugizakura-oji

In 1109, the aristocrat Fujiwara Munetada (1062-1141) wrote in his pilgrimage diary, “On the left side of the road, there was a cherry tree grafted on a Japanese cypress. It was a truly rare thing.” This is the origin of the Oji’s name: “tsugizakura” means “grafted cherry tree”.

Many gigantic Japanese Cedar trees (Cryptomeria) are located here. Some have a circumference of 8 meters and are believed to be up to 800 years old. The branches are all pointing to the south, toward Nachi Falls and the power of Kannon’s Fudaraku paradise. They are called “ipposugi”, meaning “one direction cedars”.

This shrine, along with its trees, was scheduled to be demolished in 1906 as part of the government’s shrine consolidation program. It was saved by Minakata Kumagusu (1867-1941), an eccentric genius researcher and avant-garde environmentalist. He was fiercely opposed to shrine mergers as they destroyed outstanding pockets of biodiversity, along with the beliefs and faith of the local people.

Hosshinmon-oji

Hosshinmon-oji is one of the most important sites on the Kumano Kodo pilgrimage route marking the outermost entrance into the divine precincts of the grand shrine, Kumano Hongu Taisha. Historically, there were many gates along the Kumano Kodo that were physical markers of religious ritual stages, and Hosshinmon-oji is one of these important spiritual landmarks.

“Hosshin” means “spiritual awakening” or “aspiration to enlightenment” and “mon” means “gate”. Passage through this gate was a transformational rite marking initiatory death and rebirth in the Pure Land paradise.

Mizunomi-oji

Mizunomi-oji is known as a shrine with a water source. A stone monument was erected here in 1723 by the feudal lord of the Kishu domain (present-day Wakayama prefecture). There are also small stone Jizo statues to the left of the fountain.

Jizo is a Bodhisattva, or a being that compassionately refrains from entering nirvana in order to save others, and is one of the most popular deities in Japan. Jizo is the savior and protector of children and travelers, but also takes on other forms of folk belief. The small Jizo on the right is split horizontally in the middle. People put coins in the crack and pray for relief from their backaches.

Fushiogami-oji

From the lookout point at Fushiogami-oji, pilgrims finally get the first glimpse of their goal, the Kumano Hongu Taisha. Pilgrims traditionally fell on their knees and prayed, which is what the word “Fushiogami” means. At the lowest point in the valley lies Oyunohara, the holy sandbank where the Kumano Hongu Taisha was originally located until a flood destroyed it in 1889. The salvaged remains were used to rebuild the shrine on higher ground.

There is a story that took place here at Fushiogami-oji that epitomizes Kumano. Around 1000 years ago Izumi Shikibu, a famous female poet, was on pilgrimage and started to menstruate at Fushiogami-oji. Purification is an important element in Japanese religion and blood is considered impure, so women who were menstruating were not allowed to worship. She was terribly distraught at not being able to pay homage and composed a poem in her distress.

はれやらぬ

みにうきぐものたなびきて

つきのさわりと

なるぞかなしき

Hareyaranu

Miniukigumo no tanabikite

Tsuki no sawari to

Naruzo kanashiki

Beneath unclear skies, my body

obscured by drifting clouds,

I am saddened that my monthly

obstruction has begun.

That night the Kumano deity came to her and replied

もろともに

ちりにまじわるかみなれば

つきのさわりと

なにかくるしき

Morotomoni

Chirini majiwaru kaminareba

Tsuki no sawari to

Nanika kurushiki

How could the god who mingles

with the dust

suffer because of your

monthly obstruction?

Even deities suffer from impurities, so Kumano does not exclude anyone from worshipping here. Compared with other sacred sites in Japan where women were banned, anyone was welcome in Kumano regardless of sect, class or gender. Openness and acceptance is a fundamental theme of the Kumano faith. A monument to Izumi Shikibu is located here at the lookout point.

Yunomine-oji

Yunomine Onsen is deeply connected with the Kumano pilgrimage and is linked with the Kumano Hongu Taisha via the Dainichi-goe route (1.8 km). This hot spring is famous for its healing and regenerative powers.

Yunomine-oji appears in a variety of historical pictures and records and is an important setting for the “Yunobori-shinji” rite of the Kumano Hongu Taisha’s spring festival held on April 13th. Wearing traditional costumes, fathers and sons perform ancient rituals and then walk the pilgrimage route to Hongu; the boys are carried on their father’s shoulders and not allowed to touch the ground.

Yunomine-oji used to be located within Toko-ji Temple, but after a fire in 1903 it was relocated to its present location. Toko-ji’s object of worship is a large “statue” of Yakushi Nyorai (Buddha of Healing and Medicine) made of solidified mineral deposits from the hot springs. Due to its close association with Toko-ji, Yunomine-oji differs from other Oji shrines in its connection to nature worship by means of hot spring veneration.

Kumano Pilgrimage History

Formation

Kumano has been considered a sacred site associated with nature worship since prehistoric times. When Buddhism arrived in Japan in the 6th century, this area became a site of ascetic training. As Shinto and Buddhism mixed, the belief of Kumano as a Buddhist Pure Land became prevalent. The 9th and 10th century was the formative period of the sacred sites that we know today.

Imperial Golden Age

The 11th century was believed to be the start of an era called Mappo, when the Buddha’s powers would decline and hardships would plague society. The first trip by an Emperor took place during this time. During the 11th to 13th centuries pilgrimages to Kumano by the Imperial family from Kyoto were repeated almost 100 times. With the repetitions of these large scale pilgrimages shrine buildings and accommodation facilities were constructed and improved one after another. At this time the basic scale and layout of the major buildings were consolidated. Organizations to support the area were also formed. The large number of pilgrims to Kumano far exceeded other parts of Japan.

Rise of the Samurai

The end of the 12th century saw the rise of military families and authority was taken over by a feudal government.

In the early 13th century Emperor Gotoba failed at his attempt to reclaim the ruling power. This put an end to the imperial pilgrimages but aristocrats and Samurai still came.

From the 14th to the 16th century, samurai kept a grip on the ruling authority while on various levels the struggle for power between the Imperial family and aristocrats continued. Because of Kumano’s close relationship with the Imperial capital it suffered.

In the 15th to 16th centuries the government weakened and an age of civil war and unrest took place when the feudal lords fought for power. The Shrine’s financial base was substantially taken over by those feudal lords. But because they were still considered very sacred as power changed hands the victor always faithfully made donations.

Increase in Pilgrims from the General Populace

In the 15th century because of the improved production capability and progress of the monetary economy taking place, rich citizens also began to make pilgrimages. It was also during this era that the custom of carrying out pilgrimages to sacred sites spread from samurai to the general public.

The Kumano Bikuni nuns were very active during the 16th to 18th centuries spreading the Kumano faith all over Japan.

From the 17th to the late 19th century, the powerful Tokugawa feudal government was established in Edo, present-day Tokyo. 270 years of peace ensued which was maintained under the dominance of the samurai class. With economic growth and further development of the monetary system, there was an increase in urban artisans and merchants with high incomes interested in seeing other places. They also began to make their way to Kumano. At the same time, construction and improvement of roads and other pilgrimage infrastructures including lodgings were built. Because of these developments and the safe travel situation that was created under the political stability of the Tokugawa regime, there was an increase in pilgrims.

Decline & Destruction

In the late 19th century Japan was forcefully opened to the outside world. In 1868 the Meiji Restoration saw the collapse of the feudal system and a dramatic period of change. Japan quickly evolved into a modern state to be competitive with the western countries.

The new government took strict measures to control the religions in Japan and issued the Shintoism and Buddhism separation Decree. They also prohibited Shinto-Buddhist syncretism and banned Shugendo altogether. Thousands of temples were destroyed and complexes incorporating both Shinto and Buddhist institutions forcibly separated. For example, all Buddhist-related statues and objects were removed from Kumano Hongu Taisha.

The loss of cultural artifacts was enormous, many being lost to countries overseas. In the early 20th century the government started to create cultural preservation laws. There was a dramatic drop in pilgrims leading up to and during World War Two.

After the war, the demand for timber during the economic recovery led to vast areas coming under the influence of the forestry industry and being replanted with cedar and cypress. Since 1950 the increase in development of transportation infrastructure like roads and railways drastically altered the way of pilgrimage. Large sections of the mountain route became overgrown because of disuse.

Rediscovery, Revival & Recognition

The late 1990s saw an increase in people walking the old mountain pilgrimage trails. And in 2004, with the registration of the area as UNESCO World Heritage as the “Sacred Sites and Pilgrimage Routes in the Kii Mountain Range”, the number of visitors increased dramatically. The sacred mountains of Kumano are once again being rediscovered by contemporary Japanese looking for their spiritual roots and the traditional countryside lifestyle that has been lost in modern Japanese cities.